Extractive industries that operate within or near indigenous territories

In his 2011 report, the Special Rapporteur presented a synthesis of the responses he received to a Questionnaire about extractive industries that operate within or near indigenous territories. Responses received from indigenous organizations, NGOs, companies, and governments led to the identification of the following issues related to extractive industries:

– Environmental impacts

– Social and cultural effects

– Lack of consultation and participation

– Lack of clear regulatory frameworks and other institutional weakness

– The question of tangible benefits

A/HRC/18/35 11 July 2011

CONTENTS

Introduction

22. The impact of extractive industries on indigenous peoples is a subject of special concern to the Special Rapporteur. In several country-specific5 and special reports,6 and in his review of particular cases,7 he has examined various situations in which mining, forestry, oil and natural gas extraction and hydroelectric projects have affected the lives of indigenous peoples. Also, as noted above, the Special Rapporteur’s previous thematic studies have focused on the duty of States to consult indigenous peoples and corporate responsibility, issues that invariably arise when extractive industries operate or seek to operate on or near indigenous territories.

23. In 2003, in his report to the Commission on Human Rights, the previous mandate holder examined issues associated with large-scale development projects, raising concern about the long-term effects of a certain pattern of development that entails major violations of the collective cultural, social, environmental and economic rights of indigenous peoples within the framework of the globalized market economy.

24. Since then, numerous developments have taken place in this area. In 2007, the discussion and adoption by the General Assembly of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples contributed to a greater awareness about the human rights implications for indigenous peoples of natural resource extraction and other development projects. Following the revision of World Bank policy on indigenous peoples in 2005, several international and regional financial institutions have developed their own policies and guidelines regarding public or private projects affecting indigenous peoples. Among the latest of these developments, in May 2011, OECD updated its Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises to strengthen standards for corporations in the field of international human rights, including those pertaining to indigenous peoples. Also, the International Financial Corporation has undertaken a revision of its performance standard on indigenous peoples, a process to which the Special Rapporteur contributed.

25. The work of the Special Representative of the Secretary-General on human rights and transnational corporations and other business enterprises, which has led to the development of the “Protect, Respect and Remedy” framework and the principles for its implementation, has further contributed to raising the awareness of the impact of business operations on human rights. The framework and principles, which were endorsed by the Human Rights Council in its resolution 17/4, provide further grounding for advancing in the operationalization of indigenous peoples’ rights in the context of business operations.

26. Extractive industry activities generate effects that often infringe upon indigenous peoples’ rights; public agencies and private business enterprises involved in the extraction or development of natural resources, in both developing and developed countries, have contributed to these effects. Notably, some Governments have attempted to mitigate the negative effects of extractive operations, yet human rights continue to be violated as a result of an increasing demand for resources and energy. The Special Rapporteur considers the ever-expanding operations of extractive industries to be a pressing issue for indigenous peoples on a global scale. He therefore aims to contribute to efforts to clarify and resolve the problems arising from extractive industries in relation to indigenous peoples.

A. Review of responses to the Special Rapporteur’s questionnaire

27. On 31 March 2011, the Special Rapporteur distributed a questionnaire in order to collect and understand views, concerns and recommendations relating to extractive industries operating on or near indigenous territories. The initiative was received favourably, generating a large number of responses from Governments, indigenous peoples, corporations and members of civil society. Academic experts and members of indigenous communities acting in their individual capacities also made valuable contributions to the study.

28. The Special Rapporteur cordially thanks all contributors for their detailed responses to the questionnaire and appreciates their support for his efforts to fulfil his mandate to examine ways and means of overcoming existing obstacles to the full and effective protection of the rights of indigenous peoples and to identify, exchange and promote best practices.

29. The sections below contain an overview of the main issues raised in questionnaire responses, with a primary focus on the perceived challenges created by extractive industries operating in indigenous territories. It should be noted that the Special Rapporteur requested and received examples of good practices in relation to natural resource extraction projects operating in or near indigenous territories. He continues to analyse these examples and hopes to provide further reflections on good practices in his future observations on the issue of natural resource extraction and indigenous peoples.

1. ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT

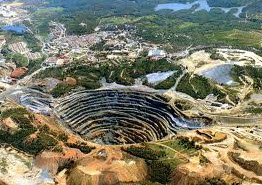

30. Responses to the Special Rapporteur’s questionnaire by States, businesses and indigenous peoples provide a detailed review of the significant impact that extractive industries have had on indigenous peoples’ lands and resources. The gradual loss of control over indigenous lands, territories and natural resources was listed by respondents as a key concern, an issue that is seen as stemming from deficient protective measures for indigenous communal lands. The majority of indigenous representatives and organizations also listed environmental impact as a principle issue of concern. Responses highlighted examples of the degradation and destruction of ecosystems caused by extractive industries, as well as the devastating resultant effects on indigenous peoples’ subsistence economies, which are closely linked to these ecosystems. Common negative environmental effects reported in the responses include the pollution of water and lands and the depletion of local flora and fauna.

31. With respect to the negative impact of extractive operations on water resources, it was noted that water resource depletion and contamination has had harmful effects on available water for drinking, farming and grazing cattle, and has affected traditional fishing and other activities, particularly in fragile natural habitats. For example, the Government of the Philippines described an open-pit mining operation in the province of Benguet, where operations had left a wasteland where “no fresh fish could ever be found in creeks and rivers”. It should be noted that reports of the adverse impact of extractive operations on water resources were not limited to exceptional cases of, for example, oil pipeline breaks. Adverse effects have also reportedly resulted from routine operations or natural causes, including the drainage of industrial waste into water systems caused by rain.

32. A number of Governments and companies highlighted the fact that a significant proportion of harmful environmental effects of extractive industry operations could be traced back to past practices that would be deemed unacceptable under current legal and extractive industry standards. For example, the Regional Association of Oil, Gas and Biofuels Sector Companies in Latin American and the Caribbean indicated that, throughout Latin America, serious environmental problems persist from the unregulated oil extraction activities that took place for more than 40 years. Similarly, the Government of Ecuador made reference to the Chevron-Texaco operations in the Amazon region, stating that the negative environmental legacy resulted from past resource exploitations that lacked regulation and control.

33. Numerous questionnaire respondents also made an explicit connection between environmental harm and the deterioration of health in local communities. Several respondents suggested that the overall health of the community had been negatively affected by water and airborne pollution. Other reports highlighted an increase in the spread of infectious disease brought about by interaction with workers or settlers immigrating into indigenous territories to work on extractive industry projects. Respondents also linked environmental degradation to the loss of traditional livelihoods, which consequently threatens food security and increases the possibility of malnutrition.

2. SOCIAL AND CULTURAL EFFECTS

35. Several indigenous and non-governmental organizations reported that the forced emigration of indigenous peoples from their traditional lands – either because of the taking of those lands or environmental degradation caused by resource extraction projects – has had an overall negative impact on indigenous cultures and social structures. One non¬governmental organization dramatically described the migration process as the transition of “ecosystem people” into “ecological refugees”. One civil society respondent from India described the negative effects of the continuous reallocation of a significant number of Adivasi and other tribal peoples as a result of large-scale developments projects, particularly dams. Many of these projects provided very little or no compensation for those forced to relocate. This problem was reported to have an especially negative effect on Adivasi women, who have apparently experienced loss of social, economic and decision-making power when removed from their traditional territorial- and forestry-based occupations.

36. According to respondents, non-indigenous migration into indigenous territories and its related consequences also have a negative effect on indigenous social structures. Examples identified by respondents of non-indigenous migration into indigenous lands include illegal settlement by loggers or miners, the influx of non-indigenous workers and industry personnel brought in to work on specific projects, and the increased traffic into indigenous lands owing to the construction of roads and other infrastructure in previously isolated areas. For its part, the Government of the Democratic Republic of the Congo expressed concern regarding the alarming rates of alcoholism and prostitution previously unheard of among the indigenous peoples. In Colombia, the arrival of extractive industries in indigenous areas has reportedly triggered the infiltration of indigenous territories by drug traffickers and guerrillas, together with the militarization of those territories.

37. Indigenous organizations and leaders reported a significant deterioration in communal social cohesion and the erosion of traditional authority structures with the increase of extractive operations. Community members often take opposing positions regarding the perceived benefits of resource extraction, resulting in conflict that, at times, erupted into violence. Social conflict appears to be particularly prevalent when economic benefits are transferred directly to individuals or limited jobs are available. Several Governments and companies also cited cases of bribery and corruption of indigenous leaders as areas of concern, although no in-depth reflection on the root causes of these patterns were included in their responses.

38. Submissions by indigenous peoples and non-governmental organizations also reported an escalation of violence by Government and private security forces as a consequence of extractive operations in indigenous territories, especially against indigenous leaders. Furthermore, a general repression of human rights was reported in situations where entire communities had voiced their opposition to extractive operations. In this connection, political instability, violent upheavals and the rise of extremist groups in indigenous areas have also reportedly resulted from the presence of extractive industries in indigenous territories.

39. Numerous questionnaire respondents highlighted the adverse effects that natural resource extraction projects operating in indigenous territories had on important aspects of indigenous culture, such as language and moral values. Additionally, respondents noted that projects had led to the destruction of places of culture and spiritual significance for indigenous peoples, including sacred sites and archaeological ruins.

40. Various respondents, including companies, recognized the need for a “different approach” when dealing with indigenous communities and extractive activities. This could include, for example, the evaluation of community-specific social and cultural effects and the development of community-specific mitigation measures. It was also suggested that cultural awareness training for company employees and subcontractors may be helpful in countering the negative impact on the social and cultural aspects of indigenous communities.

3. LACK OF CONSULTATION AND PARTICIPATION

42. Governments and business respondents provided considerable examples of social conflicts that had resulted from a lack of consultation with indigenous communities, and noted that solutions to these conflicts had invariably entailed opening a dialogue with indigenous peoples and arriving at agreements that addressed, among other issues, reparation for environmental damages and benefit-sharing.

43. Government and private-sector respondents also reported that past negative experiences often frustrated present consultations with indigenous peoples. According to the Mexican National Commission for the Development of Indigenous Peoples, as a result of past experiences, indigenous communities now fear that companies “may enter at any moment”. Lack of prior involvement, labour conflicts, unmitigated environmental damage and unfulfilled promises were identified as reasons why many indigenous communities fear or outright reject current proposals for extractive projects in their territories, even before receiving information on potential new projects or engaging in discussions about possible arrangements in this connection.

44. Several Governments provided the Special Rapporteur with information describing recent domestic legal and policy reforms that specifically relate to the regulation of the State’s duty to consult indigenous peoples regarding extractive industry activities. These reforms have entailed both the drafting of general consultation laws and policies, and

relevant revisions to “sectorial” legislation, namely, legislation relating to the use of specific resources such as minerals, forests or water resources. Some already existing mechanisms for consultation with indigenous peoples were also identified. Notably, Norway and Finland highlighted relevant domestic laws and policies that require consultations with the respective Saami Parliaments in those countries, in relation to extractive industry projects and other development plans in Saami-populated areas.

45. Although some progress is being made domestically, several responses from private business entities expressed concern over the significant level of uncertainty surrounding consultation procedures. A survey of business responses suggest that questions remain regarding the scope and implications of consultations, as well as the specific circumstances that may trigger the duty to consult. Uncertainty also remains for Governments and businesses regarding the identification of communities with whom it is necessary to consult, in particular indigenous communities whose lands have not been demarcated by the State and communities in which both indigenous and non-indigenous peoples live. The Government of Peru also observed that restricting the consultation process to communities found in direct impact areas fails to account for communities found outside those areas but that are nevertheless affected by extractive projects.

46. Various indigenous peoples’ submissions spoke to the challenges involved in obtaining accurate information about the potential impact of proposed extractive industry projects on indigenous peoples’ environment and daily lives. The Sucker Creek First Nation of Canada reported the difficulties of their communities when attempting to navigate complex information in consultation and negotiation phases. The information it provided suggested that indigenous communities may lack the technical expertise necessary to engage as equals in consultation and negotiations, which leaves them reliant on impact assessments provided by extraction companies, which reportedly do not always assess accurately the full extent of potential impact on indigenous peoples.

47. A considerable number of indigenous respondents maintain that extractive companies carry out consultations as a mere formality in order to expedite their activities within indigenous territories. In that connection, the Lubicon Lake Indian Nation in Canada indicated that the statutory duty to consult indigenous peoples had not been adequately implemented in practice to the extent that “good faith-consultations” undertaken by companies do not require the indigenous peoples’ consent or accommodation of their viewpoints. It also reported that indigenous peoples’ input does not substantively affect pre¬established Government or industry plans.

4. LACK OF CLEAR REGULATORY FRAMEWORKS AND OTHER INSTITUTIONAL WEAKNESS

49. Corporate responses point out three particular areas in which a clear regulatory framework is often lacking: the content and scope of indigenous peoples’ rights over their lands, territories and natural resources, particularly in those instances in which traditional land tenure has not been officially recognized through titling or otherwise; consultation procedures with indigenous peoples; and benefit-sharing schemes. With regard to these issues, the examples of best practices shared by companies related more to their voluntary practices and initiatives than to the meeting of the legal requirements of the countries in which they operate.

50. Business respondents and indigenous peoples noted that difficulties can arise even when domestic legal and policy standards exist, because Governments often lack the political will to implement those standards, and rather pass the responsibility on to companies and indigenous peoples. From a business perspective, this creates uncertainty and leads to additional business costs, beyond securing official permits and other administrative requirements. A number of business respondents observed the need to enter into agreements with local indigenous communities prior to launching their operations as a means of preventing future problems.

51. Additionally, information provided suggested that a lack of coordination and institutional capacity leads to insufficient operational oversight of extractive industries by States. Respondents, including Governments, observed that State institutions responsible for indigenous affairs or other relevant State institutions often worked with limited institutional and budgetary resources, resulting in limited or no oversight of extractive operations.

5. THE QUESTION OF TANGIBLE BENEFITS

B. Preliminary assessment

56. The various points of view communicated by indigenous peoples, Governments, business enterprises and other relevant stakeholders concerning natural resource and energy extractive development projects in indigenous territories reveal that, despite a growing awareness of the need to respect the rights of indigenous peoples as an integral part of those projects, many problems remain.

57. The responses to the questionnaire confirm the Special Rapporteur’s perception, derived from the various activities carried out during the first three years of his mandate, that the implementation of natural resource extraction and other development projects on or near indigenous territories has become one of the foremost concerns of indigenous peoples worldwide, and possibly also the most pervasive source of the challenges to the full exercise of their rights. Together with those of indigenous peoples’ organizations and representatives, the responses of many Governments and corporations reflect a clear understanding of the negative and even catastrophic effects on the economic, social and cultural rights of indigenous peoples due to irresponsible or negligent projects that have been or are being implemented in indigenous territories without proper guarantees or the involvement of the peoples concerned.

58. The growing awareness of the actual or potential negative impact of industry operations on the rights of indigenous peoples is further marked by an increasing number of legal regulations and other Government initiatives, as well as by enhanced action by domestic courts and human rights institutions, which were cited in the responses to the Special Rapporteur’s questionnaire. Furthermore, this growing awareness is evident in the development or strengthening by business enterprises of internal human rights safeguards and even of specific indigenous rights policies.

59. The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and the worldwide endorsement of its principles and directives, the growing empowerment of indigenous peoples to defend their internationally affirmed human rights and denounce the violations of these rights, and the lessons learned from the many negative experiences, within the context of the wider interest of the international community about the impact of business enterprises on human rights are factors that have surely contributed to this enhanced state of awareness.

60. Despite this growing level of awareness, however, the responses to the Special Rapporteur’s questionnaire also show the lack of a minimum shared understanding about the basic implications of accepted international standards or about the institutional arrangements and methodologies required to give them full effect in the context of extractive or development operations that may affect indigenous peoples. In this connection, differing or vague understandings persist about the scope and content of indigenous peoples’ rights and about the degree and nature of the responsibility of the State to ensure the protection of these rights in the context of extractive industries.

61. The current global discussion about the impact of business activities on human rights has reaffirmed that the State has the ultimate international legal responsibility to respect, protect and fulfil human rights. As much is made clear in the “Protect, Respect and Remedy”framework proposed by the Special Representative of the Secretary-General on human rights and transnational corporations and other business enterprises, which was adopted by the Human Rights Council as the basic normative structure for advancing in the protection of human rights in the context of business activities (see paragraph 25 above).

62. While an awareness and express commitment by States to the protection of the rights of indigenous peoples are evident in the many Government responses received to the Special Rapporteur’s questionnaire, these responses, coupled with those received from other sources, also reflect a lack of operative consensus about the extent and means of realization of the State’s duties with regard to resource extraction and development projects.

63. As noted above, several responses, particularly those received from business actors, pointed out that Governments tend to detach from the implementation of consultation procedures and other procedural safeguards for indigenous peoples rights in the context of extractive operations and act as mere regulators. The delegation of the State’s protective role to business enterprises was repeatedly pointed out as a matter of concern, particularly with when there are insufficient or non-existent State regulatory frameworks regarding indigenous rights, including in relation to the protection of lands and resources, consultation and benefit-sharing schemes. The lack of clarity or consensus about the role of the State in protecting the rights of indigenous peoples in this context compounds the uncertainties arising from the differing views about the scope and content of those rights.

64. An additional, significant area of divergent perspectives concerns the balance between costs and benefits of extractive development projects. Even though there is a shared awareness of the past negative effects of extractive activities for indigenous peoples, there are widely divergent perspectives about the incidence and value of benefits from extractive industries, especially into the future. As noted above, many of the Governments’ responses to the questionnaire underscored the key importance of extractive industries for their domestic economies. Many of the responses by business actors shared the view that indigenous peoples could stand to benefit from extractive industries.

65. For their part, indigenous peoples’ responses to the Special Rapporteur’s questionnaire were dominated by a great deal of scepticism and, in many cases, outright rejection, of the possibility of benefiting from extractive or development projects in their traditional territories. The vast majority of indigenous peoples’ responses, many of which stemmed from the direct experience of specific projects affecting their territories and communities, rather emphasized a common perception of disenfranchisement, ignorance of their rights and concerns on the part of States and businesses enterprises, and constant life insecurity in the face of encroaching extractive activities. Such a perception suggests that no apparent positive impact is to be had from these operations, which are seen more as a top-down imposition of decisions taken in a collusion of State and corporate interests than the result of negotiated decisions in which their communities are not directly involved.

66. In the Special Rapporteur’s view, the lack of a minimum common ground for understanding the key issues by all actors concerned entails a major barrier for the effective protection and realization of indigenous peoples’ rights in the context of extractive development projects. The lack of a common understanding among the actors concerned, including States, corporate actors and indigenous peoples themselves, coupled with the existence of numerous grey conceptual and legal areas has invariably proved to be a source of social conflict. Comparative experience, including specific country situations in which the Special Rapporteur has intervened within the framework of his mandate, provide ample examples of the eruption and escalation of these conflicts and the ensuing radicalization of positions. Where social conflicts erupt in connection with extractive or development plans in indigenous territories, everybody loses.

67. The responses to the Special Rapporteur’s questionnaire manifest the need for change in the currents state of affairs if indigenous rights standards are to have a meaningful effect on State and corporate policies and action as they relate to indigenous peoples. An initial step towards such a change is establishing a common ground of understanding among indigenous peoples, governmental actors, businesses enterprises and other relevant actors. The Special Rapporteur is conscious of the complexities inherent to any effort to harmonize the various interests involved in context of extractive industries and indigenous peoples, as well as of the difficulties in bridging the contrasting viewpoints that currently exist among the actors concerned.

68. The Special Rapporteur is, however, persuaded of the need to advance towards a minimum common understanding of the content and scope of the rights of indigenous peoples and of the implications of those rights for the future desirability or viability of extractive industries on or near indigenous territories, the nature of the responsibility of States to protect indigenous peoples’ rights in this context, the actual or potential impact of extractive industries – both positive and negative –and related matters. Without a minimum level of common understanding, the application of indigenous rights standards will continue to be contested, indigenous peoples will continue to be vulnerable to serious abuses of their individual and collective human rights, and extractive activities that affect indigenous peoples will continue to face serious social and economic problems.

C. Plan of work

69. In implementing his mandate since his appointment in 2008, the Special Rapporteur has actively pursued his core tasks of monitoring the human rights conditions of indigenous peoples worldwide and of promoting the improvement of those conditions in a spirit of cooperation and responsiveness. In doing so, the Special Rapporteur has been mindful of the directive of the Human Rights Council, namely, that he should place a particular emphasis on the promotion of good practices and technical assistance.

70. The reports submitted by the Special Rapporteur over the past three years tell of the situations in which he has intervened in particular countries in order to promote a clearer understanding of existing problems, as well as to make concrete recommendations to address those problems based on the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and other relevant international instruments. In the Special Rapporteur’s view, the numerous instances in which he has contributed actively to the process of developing new policies, legislation and constitutional reforms concerning indigenous peoples’ rights, at the request of Governments, international organizations and indigenous peoples are also significant.

71. The effects of the Special Rapporteur’s work has been clearly dependent on the capacity of the actors involved to enter into a principled dialogue in which the Special Rapporteur’s recommendations and proposals may serve as the basis for finding solutions to the identified problems within the framework of the protection of indigenous peoples’ rights. In a number of cases, his recommendations have been at least partially taken into account in the definition of State policies and legislation. The impact of the Special Rapporteur’s thematic analysis of key areas is also discernable in comparative practice, and particularly in a number of recent decisions by domestic courts.

72. In defining his plan of work for the remainder of his mandate, the Special Rapporteur is guided by a pragmatic approach that seeks to increase the practical effect of his activities within the limitations in which he operates. His experience over the past three years indicates that this can be best achieved by identifying and promoting shared understandings of the basic contents of indigenous peoples’ rights, as well as to provide practical guidance on how to operationalize them.

73. As pointed out above, the question of the rights of indigenous peoples in the context of natural resource extraction and development projects has invariably emerged during his activities as a major area of concern and potential human rights abuse. The responses to the Special Rapporteur’s questionnaire, significant both in number and in quality, have provided the Special Rapporteur with a clear indication of the need to continue working in this area.

74. In this respect, the Special Rapporteur believes that an effective way to advance in the fulfilment of his mandate during the years ahead is to focus on the elaboration of a set of guidelines or principles that will provide specific orientation to Governments, indigenous peoples and corporations regarding the protection of indigenous rights in the context of resource extraction or development projects. The need for specific guidelines was underlined in several of the responses to the Special Rapporteur’s questionnaire, particularly those from Governments and several business corporations and associations.

75. The elaboration of a set of guidelines or principles that operationalize the scope and content of the rights of indigenous peoples in the context of development or extractive projects affecting their territories, as well as of the kind of institutional measures required to guarantee the enjoyment of those rights in this context, is fully consistent with the particular emphasis that the Special Rapporteur’s mandate places on the promotion of best practices and the provision of technical assistance to Governments.

76. Moreover, this line of action is directly connected to the kind of operational measures required by the guiding principles on business and human rights within the “Protect, Respect and Remedy” framework recently endorsed by the Human Rights Council in its resolution 17/4. The guiding principles specify that States, as part of their duty to protect human rights in the context of business enterprises, should “enforce laws that are aimed at, or have the effect of, requiring business enterprises to respect human rights” while also providing “effective guidance to corporate actors” on how to respect human rights throughout their operations.

77. In his commentaries to these principles, the Special Representative of the Secretary- General emphasized that the fulfilment of State’s duties in this context requires greater clarity in some areas of law and policy, such as those governing access to land, including entitlements in relation to ownership or use of land.13 Furthermore, he noted the need for States to provide “clear guidance to business enterprises on respecting human rights”, including methods to enhance human rights due diligence that recognize the “specific challenges that may be faced by indigenous peoples”.

78. Working towards the operationalization of indigenous peoples rights and of the institutional safeguard required to make them effective in the context of natural resource extraction or development projects could constitute, in the Special Rapporteur’s view, a useful tool in the hands of indigenous peoples and Governments when they define more effective legal frameworks and policies in this area, and also to provide guidance to corporate actors in this regard.

79. While continuing to work in the fulfilment of all the areas of work defined by his mandate, the Special Rapporteur’s work towards the operationalization of indigenous peoples’ rights in the context of extractive projects will require a rerouting of significant efforts and of human and material resources. As stated above, the Special Rapporteur considers of utmost importance the bridging of the divergent viewpoints of States, indigenous peoples and corporate actors in this regard, which necessarily entails the opening of a process of wide consultations and dialogue with all the actors concerned. Expert consultations and studies on specific areas will also be required to promote an understanding of indigenous peoples’ rights that is effective and practicable within the domestic policy frameworks and business practices in which these projects are implemented.

80. Many debates will ensue, and are surely required, concerning the existing extractive model and its broader social and environmental impact. In the meantime, indigenous peoples will continue to be vulnerable to human rights abuse, which erodes the basis of their self-determination and, in some cases, endangers their very existence as distinct peoples. In this connection, the Special Rapporteur fully adheres to the kind of “principled pragmatism” assumed by the Special Representative of the Secretary-General on human rights and transnational corporations and other business enterprises: “an unflinching commitment to the principle of strengthening the promotion and protection of human rights as it relates to business, coupled with a pragmatic attachment to what works best in creating change where it matters most – in the daily lives of people.”